Are we Solving the right Problems?

November 18, 2024

Unconventional CPS Series I

In our previous post, “Innovative by Design: creativity to tackle complex problems”, we explored the importance of creativity in the context of innovation and problem-solving. By doing so, we deliberately fell into one of the most common human pitfalls for complex problem solving: we went straight for the solution.

The fact is, activating our “ problem-solving mode” is something that we, as humans, are designed to do. We engage in problem-solving as an immediate, almost reflexive response to challenges. This is part of our behavioral design, where cognitive processes trigger the emission of problem-solving actions as soon as a challenge is perceived, using previous experience and mental shortcuts to seek fast resolution (Binder, 1996; Taylor & Edwards, 2021).

This incredible feature has helped us survive over the millenia, helping us quickly tackle challenges affecting our daily lives. However, in today’s interconnected business world, this instinct can be more of a bug than a feature.Our natural urge to solve problems immediately tends to lead us to quick, surface-level fixes rather than more strategic and thoughtful solutions.

In 2012, Dwayne Spradlin published an article in Harvard Business Review, questioning the reader: “Are You Solving the Right Problem?” (Spradlin, 2012). In the article, the author emphasized the importance of rigorously defining problems to ensure organizations address the right challenges, therefore avoiding wasted resources and missed opportunities. Spradlin proposed a four-step method that became known as the Problem Definition Process to help organizations identify, articulate, and solve the right problems through a structured approach that involves asking the right questions and engaging diverse solvers.

This is not the only instance focused on the importance of Problem Definition. In fact, the topic of defining a problem correctly has been recurring in the literature for many years already: Ramirez (2002); Nickols(2004); Wedell-Wedellsborg (2017); Christensen (2018); Bianchi & Verganti (2021), among many others, highlighted the importance of the correct definition of the problem as a means to uncover hidden aspects, consider alternative solutions, and align efforts with real-world needs.

As we explored in our previous post, creativity can be a wonderful tool to assess complex problems, such as the definition of the problem in itself. Here, we’ll explore the application of combining divergent and convergent thinking, a standard in the areas of innovation in design and design thinking: IDEOU Blog (2017); Childs et al (2022); IDEOU (2024), to search for and define the problem statement that will act as the north star in our problem-solving process.

Creativity applied to the problem definition

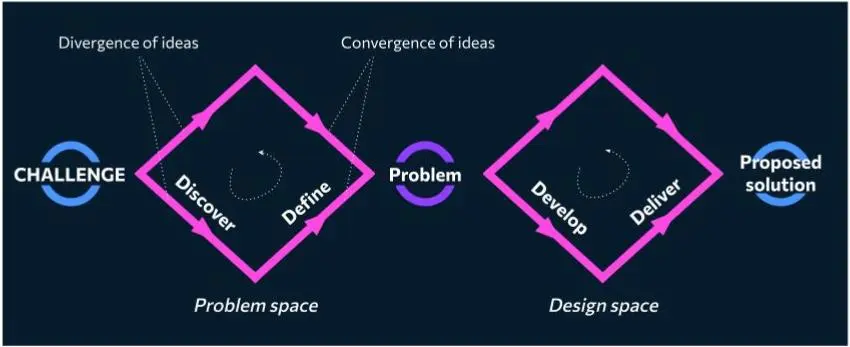

For those of you who might be new to the concepts of convergent and divergent thinking, the Double Diamond Framework from the Framework from Innovation of the Design Council (2024) can be particularly enlightening. The Double Diamond is a very visual framework that represents the innovation process through 4 stages and 2 loops of divergent and convergent thinking: Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver. For the purposes of this post, we present an adaptation and simplification of the framework in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Adaptation of the Double Diamond Framework (Design Council)

Figure 1: Adaptation of the Double Diamond Framework (Design Council)

The Double Diamond, as some of the references indicated above, emphasizes the importance of defining the correct problem through rigorous exploration and refinement. This is done during the first diamond, which refers to the Problem space. In an upcoming post in the series, we will delve deeper into the second diamond, which refers to the Design space.

For problem definition, the framework proposes applying divergent thinking to explore as many aspects as we can (Discover), that is, opening up the challenge for questioning. Overall, this first stage is about gathering as much information as possible via research, observation, and engagement with stakeholders to understand their needs, challenges, and behaviors. It requires broad exploration, being open to all possibilities, and questioning initial assumptions to provide a wide problem space.

Next, the framework switches to convergent mode to be able to define precisely our central question (Define). After gathering insights, this stage involves synthesizing the information to redefine the problem more accurately. This means filtering the data to identify the core issue and formulating an adequate, goal-oriented and precise problem statement.

One of the key aspects that you may note is the accent that is put into the involvement of stakeholders. Aside from the people who are trying to solve the problem, we must also account for those people who will be affected directly or indirectly by the different solutions to the challenge, and those who might be a part of the problem themselves. We are talking about the impact of people’s opinions, experiences and feelings here, therefore encountering one of our usual suspects in Unconventional CPS: the X Factor.

The X factor and the impact of cognitive biases in problem definition

There is one aspect in human psychology that severely impacts the problem definition: our very own cognitive biases. Cognitive biases are systematic patterns that deviate the rationality in our judgment, often occurring subconsciously. These biases affect how we perceive information, make decisions, and define problems. In the context of problem-definition, cognitive biases can significantly distort our understanding of the problem space, leading to a suboptimal definition of the problem that might end up in misaligned solutions and wasted efforts.

Understanding, recognizing and mitigating these biases is crucial for ensuring that the defined problem reflects the true underlying issues, rather than skewed perceptions influenced by our preconceived notions. Particularly, there is one bias that explains our tendency to jump directly into problem-solving without adequately exploring or understanding the problem: It’s the plunging-in bias, a rush that normally leads to addressing symptoms rather than root causes.

The plunging-in bias was close to killing an iconic brand such as Harley-Davidson (Bhardwaj et al., 2018). In the 1980s, the company faced severe challenges, including competition from Japanese manufacturers, poor product quality, and financial losses. Harley's leadership jumped into conclusions and misidentified the root cause of their struggles, attributing their failures to external factors like Japanese culture, automation, and market dumping practices. Only after years of misaligned solutions and continued struggles, the leadership recognized that the real problem was internal—Harley-Davidson's own practices and strategic approach needed to change. This delay in identifying the correct problem exemplifies how plunging into the solution without proper analysis can lead to ineffective outcomes and prolonged difficulties.

Bhardwaj et al. (2018) explain that the Harley-Davidson case is far from unique. Their study of 356 decisions in medium-to-large organizations found that about half of the decisions fail due to rushed problem-solving approaches. Key reasons included jumping to conclusions, limiting the search for information, and imposing pre-determined solutions without adequate exploration of the problem space. Some of these are in themselves well-known cognitive biases, such as the Anchoring Bias (relying heavily on the first relevant piece of information encountered, and taking it from there), the Fixation Bias (that prevents individuals from thinking beyond established solutions and default to conventional approaches, limiting creativity) and the Confirmation Bias (that leads individuals to search for, interpret, and remember information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs, while disregarding contradictory evidence).

Design thinking techniques have been shown to contribute in overcoming some of these biases. For example, a study by Hookway et al (2019) showed that biases such as the Egocentric Empathy Gap (individuals assuming that others perceive and value problems similarly to themselves, neglecting diverse user perspectives) and the Focusing Illusion (individuals concentrating on one aspect of a problem, often due to emotional or situational reasons, at the expense of other critical aspects) were common in the healthcare industry and could be successfully tackled via problem reframing. Not surprisingly though, design thinkers themselves have their own biases inherent to their human nature that can manifest in ways such as the Projection Bias (projecting one’s own emotions, thoughts, or beliefs onto others, assuming they will react in the same way).

Therefore, as we problem-definers/problem-solvers are still all human by now (hope you don’t mind, LLMs), we need to determine some ways to objectively and actively avoid their effects in a structured, as-bias-free-as-possible way. At Unconventional CPS, as we already hinted before, we apply problem reframing techniques and are constantly learning and training in new ways to help our customers in this challenging task.

Discovering the problem space with CPS

Problem reframing, in essence, is a divergent process that redefines or shifts how a problem is perceived to uncover new perspectives, alternative solutions and deeper insights. It involves challenging the human biases, applying technology to enhance objectiveness, understanding how complex systems work, leveraging business knowledge and sneak-peeking into the future to explore the problem from different angles. In our experience, this multidisciplinary approach leads to more innovative and effective solutions.

In order to challenge inherent human biases, we question the default view of the problem to reveal underlying issues that are not immediately apparent or might be hindered by our deep personal beliefs. To do so, we encourage the incorporation of the views of as many stakeholders as possible; note that, the more diverse the viewpoints, the better (see Murphy, 2023).

To enhance this process, several tools and techniques can be used. Brainstorming, for example, is a well-known method to generate a large number of ideas in a short period. Several brainstorming techniques such as sticky notes, grid brainstorming, brainwriting, among others, can be combined for an enhanced flow of ideas. Analogous inspiration (see the IDEOU Blog) consisting in drawing parallels between the challenge and unrelated concepts can be extremely helpful by extrapolating the knowledge we have acquired when working in different industries and combining it with the specific business knowledge from our customer. Mind mapping and role playing are among other techniques that promote creativity and release preconceived ideas using visual hunches and game dynamics. It's very important to highlight that, as Childs et al. (2022) explain, any of these processes require deferring judgment and encouraging free-flowing ideas to foster creativity and maximize success.

Next, we put technology at the core. After almost 30 years in the market, our team of over 1300 sngulars has a strong connection to the tech environment and covers over 60 areas of technological expertise. Particularly, our Unconventional CPS initiative stems from the know-how we have acquired when applying the latest technological advances to industries such as financial services, retail, healthcare, telco, manufacturing, infrastructures… As a result, during the problem reframing phase we apply AI at a strategic level, and extend the use technology for problem reframing by comprehensively gathering data, carrying out expert analysis and extract insights from data analytics to explore and understand the problem space, uncovering patterns and anomalies that human-only analysis might miss.

Our next area of action comes from the acknowledgment that complex challenges are, in essence, systems. Therefore, we use systematic means to explore the problem space and apply systems engineering tools for the matter. There are well known systemic tools for creative thinking that can be applied to define and explore the problem and design spaces (see e.g. Childs, 2018), such as TRIZ, which stands for the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving. With a strong relationship to technology, TRIZ was originally developed in 1946 by Genrich Altshuller and is based on the systemic analysis of millions of patents throughout history to provide shortcuts to diverse experiences applying a combination of 40 principles and 39 parameters. Another systematic approach to systematic idea exploration is SCAMPER, which stands for Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to other use, Eliminate and Rearrange (see, for example, the article on SCAMPER from the Interaction Design Foundation, 2024). Fundamentally, it consists of applying questions systematically to existing knowledge and initial hunches to uncover possible ways of exploration.

Beyond design thinking, systems engineering is a well-established discipline that has been applied recurrently to some of the most complex challenges in humanity. Ever heard of “you should be able to do that, it’s not rocket science!”? Well, rocket-scientists put a particular emphasis in applying systems engineering as a way to tackle challenges that humanity had not dared before, as you can see for example in the Systems Engineering Handbook by NASA (2007). With regards to the Discovery phase and the exploration to better understand our challenge, the Handbook proposes a systemic process to define the expectations of the Stakeholders (see, pp 45-53). It’s the Stakeholder Expectations Definition Process which includes a whole set of concepts, procedures, and mechanisms to “identify who the stakeholders are and how they intend to use the product”. Similarly, the Systems Engineering Body of Knowledge (SEBoK) by the SEBoK Editorial Board (2024), a key reference in the domain, has a section specifically on Identifying and Understanding Problems and Opportunities. So we can observe that, even in disciplines so seemingly distinct as digital product design and rocket science, the correct identification of our problem is a key factor in a successful problem-solving process.

Our fourth area of exploration is the business acumen of all of the stakeholders. Aside from the goals, objectives and incentives that any of the stakeholders have to participate in the resolution of the challenge, and working beyond their inherent biases, there is an obvious and undeniable value on their knowledge of the business area at hand that must not be overlooked. Business leaders with strong acumen normally excel at framing and reframing problems in an natural way. They can view problems from multiple angles, recognizing underlying business implications and opportunities often missed by more linear approaches. Complex problems often involve unpredictable dynamics and competing interests. Business acumen helps in assessing risks and prioritizing actions, and enhances holistic problem-definition.

Finally, during the Discovery phase we need to acknowledge the importance of the future. We might not be able to know what the future will bring us, but at least we need to make an effort in foresighting it. Our problem definition, and hence our later explorations of the design space, need to lead to solutions that must not only be resilient, but also able to adapt to the upcoming changes.

Inayatullah (2008) presented a comprehensive and systematic approach to studying the future and projecting the knowledge acquired into the present. Foresighting helps us in our problem definition process by providing a structured way to explore possible futures, identify underlying assumptions, and consider alternative scenarios. To do so, we can use tools such as the Futures Triangle to map the forces shaping the future, highlighting the pulls, pushes, and weights that affect the current situation. The Futures Triangle is a tool that helps in defining a problem by analyzing three forces that act over it.

First is the pull of the future, the image or vision of the future that pulls people forward. It requires identifying the stakeholders’ aspirations and their desired outcomes. Next is the push of the present, current trends and drivers that push change forward. Understanding these helps to identify existing pressures and dynamics that shape the problem. Finally, the weight of the past introduces barriers or historical constraints that hold back progress and can become an obstacle to desired change.

In Unconventional CPS we have identified several of these actors that we normally refer to as attractors. The impact of attractors is capital on the accurate definition of a problem, with some of them (such as technological megatrends and accelerated business models) as instances of the push of the present, while others such as hyperpersonal spaces, personotechnics and the sustainable goals for our planet are instances of the impact of the future pulling on today.

Embracing a new way of solving complex problems

As we continue exploring together the intricacies of complex problem-solving, we’ll wrap up this post by presenting some of the key outcomes that we have discussed:

-

Finding a truly effective solution requires an initial stage of understanding and defining the problem correctly from the start. We need to move beyond the human tendency of jumping straight into solutions, and shift our mindset to place greater emphasis on the exploration and precise definition of problems as a foundation of impactful and sustainable innovation.

-

Our Unconventional CPS initiative continuously refines and grows our toolbox by integrating the latest insights from design thinking, cognitive science, and systems engineering to redefine how we approach complex challenges. By embracing problem reframing techniques, leveraging technological advancements, and involving diverse stakeholder perspectives, we aim to help our customers navigate the complexities of today's dynamic business landscape.

-

Unconventional CPS is not just about solving problems, but rather about understanding the deeper, hidden dimensions of the challenges our customers face. By shifting our focus from immediate fixes to a thorough exploration of the problem space, we unlock opportunities for more innovative, adaptive, and resilient solutions.

Our commitment to redefining the problem-solving journey doesn't stop here. In the next part of our series, we will delve into the second half of the Double Diamond Framework—the Design Space—where we will explore how creativity and structured innovation techniques can be used to develop solutions that are effective for today and built to thrive in the future.

You are more than invited to join us in redefining your approach to challenges, ensuring that we are not just solving problems, but solving the right problems in ways that truly matter to you.

References

Binder, C. (1996). Behavioral fluency: Evolution of a new paradigm. The Behavior Analyst, 19, 163–197

Taylor, T., & Edwards, T. L. (2021). What can we learn by treating perspective taking as problem solving? Perspectives on Behavior Science, 44 , 359-387.

Spradlin, D. (2012). Are You Solving the Right Problem? Harvard Business Review.

Ramirez, V. E. (2002). Finding the Right Problem. Asia Pacific Education Review, 3(1), 18-23.

Nickols, F. (2004). Choosing the Right Problem Solving Approach.

Wedell-Wedellsborg, T. (2017). Are you solving the right problems? Harvard Business Review, 95(1), 76-83.

Christensen, I. (2018). New Product Fumbles: Organizing for the Ramp-up Process. Copenhagen Business School. PhD Series No. 13.2018.

Bianchi, M., & Verganti, R. (2021). Entrepreneurs as designers of problems worth solving. Journal of Business Venturing Design, 1, 100006.

IDEOU Blog (2017). Divergent Thinking and the Innovation Funnel.

Childs, P., Han, J., Chen, L., Jiang, P., Wang, P., Park, D., Yin, Y., Dieckmann, E., & Vilanova, I. (2022). The Creativity Diamond—A framework to aid creativity. Journal of Intelligence, 10(4), 73.

IDEOU (2024) Creative Thinking for Complex Problem Solving, Online course.

Design Council. (2024). Framework for Innovation. Design Council.

Bhardwaj, G., Crocker, A., Sims, J., & Wang, R. D. (2018). How to Beat a Little-known Bias that Plagues Problem-Solvers. Academy of Management Insights.

Denyer Willis, L., & Chandler, C. (2019). Quick fix for care, productivity, hygiene, and inequality: Reframing the entrenched problem of antibiotic overuse. BMJ Global Health.

Kim, E., Purzer, S., Vivas-Valencia, C., Payne, L. B., & Kong, N. (2020). Problem Reframing and Empathy Manifestation in the Innovation Process. American Society for Engineering Education.

Nessler, D. (2016). How to Apply a Design Thinking, HCD, UX or Any Creative Process from Scratch. Digital Experience Design, Medium.

Bhardwaj, Gaurab & Crocker, Alia & Sims, Jonathan & Wang, Richard. (2018). Alleviating the Plunging-In Bias, Elevating Strategic Problem Solving. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 17.

Nessler, D. (2020). Fail, Reflect, Iterate: Rethinking the Design Process. Phase Mag,

Hookway, S., Johansson, M. F., Svensson, A., & Heiden, B. (2019). The Problem with Problems: Reframing and Cognitive Bias in Healthcare Innovation. The Design Journal, 22(Sup1), 553-574.

Todd, E. M., Higgs, C. A., & Mumford, M. D. (2019). Bias and Bias Remediation in Creative Problem-Solving: Managing Biases through Forecasting. Creativity Research Journal, 31(1), 1-14.

Design Council. (2023). 20 Years of Building on the Double Diamond. Medium.

Murphy, L. R. (2023). Pursuing Inclusive Engineering Design: Centering People, Exploring Diverse Perspectives, and Promoting Divergent Thinking. PhD Thesis. University of Michigan.

Childs P. (2018), Mechanical Design Engineering Handbook, 2nd Edition - November 24, 2018, ISBN: 9780081023679

Interaction Design Foundation (2024), Scamper: How to Use the Best Ideation Methods, Accessed online 30-08-2024,

NASA (2007) Systems Engineering Handbook, Accessed online 30-08-2024,

SEBoK Editorial Board (2024). The Guide to the Systems Engineering Body of Knowledge (SEBoK), v. 2.10, N. Hutchison (Editor in Chief). Hoboken, NJ: The Trustees of the Stevens Institute of Technology. Accessed online 30-08-2024,

Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: Futures thinking for transforming. Foresight, 10(1), 4-21..

Our latest news

Interested in learning more about how we are constantly adapting to the new digital frontier?

Insight

October 24, 2024

Innovative by Design: creativity to tackle complex problems

Corporate news

April 22, 2024

Javier Recuenco, new Strategy Advisor at SNGULAR

Corporate news

April 2, 2024

Awaken the sleeping giant of your company!